Forever 16: The inquest into Cleveland Dodd’s death in custody hears WA youth detention in crisis

Key points:

- Cleveland Dodd, 16, died after being held in an adult prison. The inquest into his death resumes this week and his family wants answers.

- Megan Krakouer, from the National Suicide Prevention and Trauma Recovery Project, said Cleveland’s devastated family is angry about the way he was let down.

- The teen was partially revived and taken to hospital but suffered a brain injury due to a lack of oxygen.

Warning: this article contains the name of an Aboriginal person who has died.

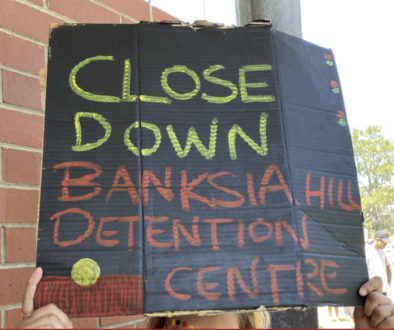

People hold placards during a rally calling for justice following the death of teenager Cleveland Dodd. (Credit: AAP Image/Aaron Bunch)

Cleveland Dodd’s family say they are heartbroken and still grieving the loss of their boy, who died in custody aged just 16.

The Yamatji boy was found unresponsive after harming himself inside his cell in a wing of a high-security adult prison, where children were being held, in the early hours of October 12, 2023.

Cleveland was taken to hospital in a critical condition and died about one week later, causing outrage and grief in the community.

Megan Krakouer, from the National Suicide Prevention and Trauma Recovery Project, said Cleveland’s devastated family is angry about the way he was let down.

“This was an avoidable death,” she said.

“They are angry, we are angry, our Black community across this country are angry, our allies are angry.”

Cries for help ignored

The inquest’s first sitting in April heard Cleveland made eight threats to self-harm and numerous requests for medical treatment and drinking water in the hours before he was discovered in Unit 18 at Perth’s Casuarina Prison.

Night-shift staff ignored those requests because a senior officer informed them Cleveland had been given six cups of water with his dinner and his cell was not to be unlocked.

But CCTV footage shows Cleveland was given only three cups of water when his evening meal was delivered to his cell about 6pm, along with a bladder of milk.

Cleveland’s threats to self-harm on October 11 and 12 started after his fifth request for water was ignored.

He had also covered a CCTV camera in his cell with tissue paper, blocking the view of correctional staff monitoring him from a control room, but it wasn’t uncovered until they were fighting to save his life.

Officers were generally reluctant to open detainees’ cell doors at night “due to staffing numbers and risk issues” but a guard did visit Cleveland’s cell and speak to him through the door before moving on to check on another detainee.

It was about this time Cleveland self-harmed.

A video shows a staff member banging on Cleveland’s cell door soon after, but he didn’t have keys to open it or a radio to call for help.

The officer left Cleveland and walked to a manager’s office on another floor to collect the keys.

At 1.51am, the same guard returned to Cleveland’s cell and opened the door.

Cleveland Dodd, 16, died after being found unresponsive in his cell at Unit 18. Source: (Supplied / Approved and Supplied by Mr Dodd’s family)

A code red alert was issued at 1.54am as staff tried to revive the teen.

Paramedics arrived at 2.06am but did not get access to Cleveland, who was found to be in cardiac arrest, for nine minutes.

The teen was partially revived and taken to hospital but suffered a brain injury due to a lack of oxygen.

He died, surrounded by his family, on October 19.

On Monday, when the inquest resumed in Perth, former inspector of custodial services Neil Morgan said Western Australia’s youth detention facilities had been in crisis for more than a decade and the justice department had forgotten it was dealing with children.

“We must treat children as children,” he told the coroner.

“We should stop trying to demonise, blame and break them.”

Professor Morgan said it was “time for the department to stop breaking the law” following two Supreme Court rulings against it.

“There’s been no sense that locking children up for upwards of 20 to 23 hours a day will somehow have a deleterious impact on them,” he said.

Aboriginal Legal Service director Peter Collins told the court two weeks before Cleveland died, his office had requested the department transfer the teen from Unit 18 to Banksia Hill Youth Detention Centre but received no response.

The letter said conditions at Unit 18 were affecting Cleveland’s wellbeing, he wasn’t able to access education and was being locked in his cell for long periods.

Mr Collins said the department failed to reply to most of the ALS’s letters, including one that raised concerns about the unit over frequent lockdowns, lack of access to education and inadequate mental health support and responses to serious harm.

He said the department transferred youth detainees to Unit 18 “under a cloak of secrecy” and it had failed to respond to questions about the closure of the unit, which was set up as a temporary facility.

Mr Collins said the facility was painted as a “silver bullet” to end the problems at Banksia Hill “but the reality couldn’t be further from the truth”.

He said detainees had been “demonised” as murderers and rapists and the facility wasn’t therapeutic or rehabilitative as promised.

Damaging to mental health

He said isolating vulnerable young Aboriginal detainees at the unit was damaging to their mental health.

“Connection to family, that social and familial interaction on a daily basis with your community underpins your entire existence,” he said.

“To then be cast into a situation in Unit 18, on your own, in a cell for hours on end, with very limited out-of-cell time, confined … with little or no interaction with other young people.”

Outside the court, Cleveland’s family and supporters vented their frustration and anger after Coroner Philip Urquhart excused a key witness from giving evidence over fears for his mental health.

Unit 18’s senior officer in charge the night the Cleveland self-harmed, Kyle Mead-Hunter, was found partially clothed in a darkened office by a lower-ranking officer after the teen was found in distress.

Cleveland’s grandmother Glenda Mippy said she was disgusted.

“He was the one who was sleeping on the job … we wanted to hear from him,” she said.

The second sitting of an expedited inquest in Perth examining Cleveland’s death began on Monday and is scheduled to run until August 9.

13YARN 13 92 76

Lifeline 13 11 14

Contact us

Please provide a brief description of your claim.