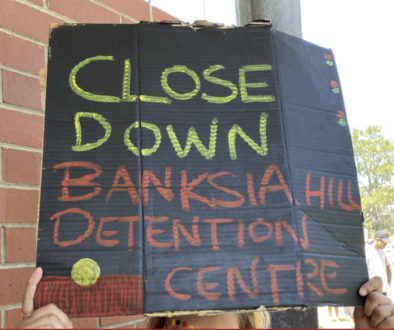

Cleveland Dodd’s death in Unit 18 was entirely foreseeable — yet no-one stopped it

Key points:

- Cleveland Dodd’s death highlights specific procedural oversights and operational shortcomings

- Stakeholders say it demonstrates a desperate need for substantial reforms

- The tragic outcome was foreseeable due to a culmination of warning signs

WARNING: This story discusses incidents of self-harm and the image of an Indigenous person who has died.

For the last three weeks, the WA government has been trying to convince you what happened inside Unit 18 on the night Cleveland Dodd died was an array of things.

A tragedy that was somewhat inevitable because of how “challenging, complex and frequently dangerous” those sent to the notorious youth detention unit are.

An isolated incident that doesn’t reflect on the bigger system.

A confronting episode that guards working that night had handled impeccably.

Now we know it was none of those things.

The wasted opportunities

Not only were there dozens of missed opportunities to avoid Cleveland’s death in the years prior, we now know there were at least half a dozen points at which it could have been averted in the immediate lead-up.

That those chances were missed, and 16-year-old Cleveland became the first recorded death in WA’s youth detention system, shows a failing system in desperate need of change.

Mere hours after Cleveland had been resuscitated, Corrective Services Minister Paul Papalia confidently praised the actions of the guards who responded.

“The boy had contacted officers via the intercom. It was only a matter of minutes from that moment until he was checked and found to be unresponsive and the officers commenced resuscitation,” was the minister’s version of events.

That “matter of minutes”, it has now emerged, was 16 minutes.

At least three times across two days Mr Papalia praised the conduct of the officers, saying he was “full of admiration” for what they had done.

But he hasn’t repeated the comments since October 17 – perhaps because of the allegations that have now surfaced.

Those allegations bring into sharp focus questions about whether Cleveland might have stood a chance of a better outcome had a plethora of things gone differently.

Oblivious to suicide warnings

Maybe he might have been found sooner if the guard checking on detainees had been given a radio and officers in the control room had been able to communicate with him.

Instead, he seems to have been oblivious to the warnings Cleveland had just given them about his intention to self-harm.

That same radio could have saved critically important seconds in opening Cleveland’s cell door and starting CPR once the officer realised what had happened.

Guards might have swung into action sooner if they had removed the piece of toilet paper covering the camera in Cleveland’s cell and were able to monitor him in real-time.

The whole situation might have been avoided if he had been moved from the cell with the damaged air vent in the days prior, as he was meant to have been.

Things could have turned out differently if workers tasked with repairing that vent hadn’t left without fixing it the day Cleveland took his life.

None of that happened, and we now know what the consequence was.

The failures of individuals on the night in question clearly need to be examined, as they undoubtedly will be by all of the inquiries probing Cleveland’s death.

But they are not the entirety of the problems. They are just the beginning.

Systemic failure to protect children

Those failures occurred within a much larger system, which is meant to protect some of the most vulnerable children in the state from themselves and from those who they might harm.

Unit 18 was meant to be the safest place possible to accommodate them.

Instead, a 16-year-old boy was able to take his own life within its walls.

A well-designed system would account for the possibility of failures at every level, with defences in place to stop any individual events compounding into a bigger catastrophe.

What has now been revealed shows how those defences either failed or were missing entirely.

Cleveland’s death did more than highlight the failures of officers that night — it shone on spotlight on the broken system they were working within.

A system that meant individual and seemingly innocuous errors on the night — which appear to have been habitual shortcuts made by those trying to work in that broken system — added up to disaster.

Things like not carrying radios on the night shift, allowing detainees to cover their cameras and pre-filling welfare check forms.

There’s little room to argue anyone could be surprised by those failures, and the cracks Cleveland fell through.

At all levels, the government could hardly have been warned more.

An entirely foreseeable outcome

Employees within the Department of Justice, including those directly responsible for the management of Unit 18, knew about some of the poor habits of staff on the ground.

At a higher level, the government had been warned at length by basically everyone involved about how precariously close the system was to letting someone like Cleveland fall through the cracks.

Courts at various levels have laboured the point for a year-and-a-half, including the president of the Children’s Court Hylton Quail.

Last month he described how time in detention “brutalised and alienated” vulnerable young people while subjecting them to “extrajudicial and unlawful punishment”, rather than helping them turn their lives around.

The Disability Royal Commission was searing in its assessment of the department’s handling of long-standing staffing issues and a culture of blaming detainees for acting out as a result of conditions they are subjected to.

Two weeks before Cleveland died, the Aboriginal Legal Service wrote to those responsible for Unit 18 in a desperate bid to raise concerns about his welfare – a warning which seemingly fell on deaf ears without any substantive response given.

Mr Papalia went as far as saying there was “nothing in that letter that was new”.

The list goes on.

Cleveland’s death was not unexpected, or without warning, or a sudden freak occurrence.

It was an entirely foreseeable consequence of those gaps slowly getting bigger over time, until one was large enough for Cleveland to slip right through, undetected for at least 10 minutes.

The next Cleveland

When Mr Papalia announced last month Assistant Police Commissioner Brad Royce would be the new Corrective Services Commissioner, there were plenty of references to a “culture” that needed to be fixed.

Premier Roger Cook wouldn’t elaborate much further when pressed on what those cultural problems were.

What has now been exposed gives some strong indications of where his work might need to begin.

But the government cannot say it has solved those problems by swapping out the people in charge.

They will linger at every level until real change is brought about.

Maybe it will be achieved by those fresh faces. Maybe it won’t.

But until those holes start to be closed, the harsh reality is there could be another young person waiting to take their own life in detention.

And there would be every chance they would slip through the same blood-stained cracks as Cleveland did.

Contact us

Please provide a brief description of your claim.