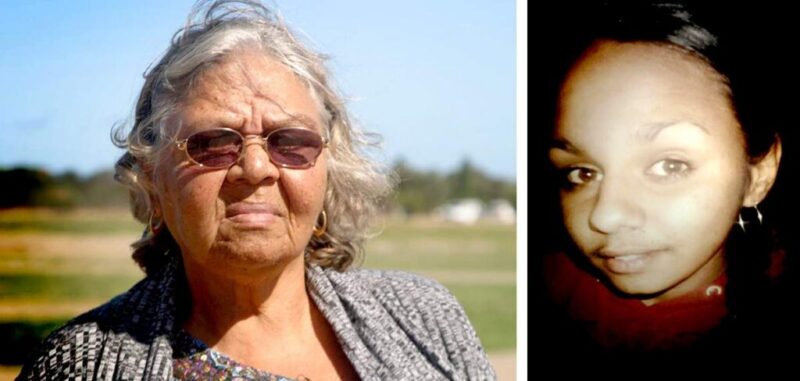

Paying with her life: Justice for Julieka Dhu

WARNING: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander viewers are advised that the following article contains images of deceased persons.

A young Aboriginal woman lies dying in agony on the floor of a police lock-up while officers laugh, mock her as a “junkie” and accuse her of “faking” her fatal illness. How can this still be happening in Australia, 25 years after the report of the Royal Commission into Black Deaths in Custody was supposed to put an end to it?

You can see the grave from the porch of the little fibro-clad cottage where Carol Roe lives with a clutter of children from her extended family. It’s less than 100 metres away, across the road and through the newly-erected wire fence that surrounds the cemetery of the Western Australian port of Geraldton.

Lot number 7919 is carpeted with a rainbow of coloured plastic flowers, and at night solar-powered fairy lights illuminate it. But there is no gravestone yet at its head – that will have to wait until the unyielding brick-red soil of the Yamatji Country of Carol’s ancestors has sunk to a stable level.

This is the last resting place of Carol’s dearly-loved granddaughter Julieka Dhu*, the “bright, bubbly” girl she cared for during most of her childhood, and buried here nearly two years ago, dead at the age of 22.

Carol Roe doesn’t celebrate Christmas nowadays – no decorations, no turkey – because Julieka’s birthday was the following day, Boxing Day 1991. Instead, she walks across the road and sits by the grave with tears running down her face as she remembers sitting in a Perth courthouse watching the ghastly videos of her granddaughter sobbing, groaning and begging for help as she lay dying on the concrete floor of a police cell.

In the background someone can be heard laughing. A witness tells the inquest that a police sergeant stoops down and whispers in Julieka’s ear that she is a “f—- junkie” and “faking” her agony. Asked to help, a policewoman says “I am not going to hurt my back for her.” They drag the helpless young woman from her cell “like a dead kangaroo,” gasps her mother, from the court’s public gallery. An hour later she is pronounced dead.

“We want justice for Julieka,” says Carol, clutching a poster calling for a National Day of Action as she takes me to the grave. “They let her die like a dog. We want to see the police, the medical people and the mongrel who hurt her in the first place brought to justice.”

Twenty five years after the Royal Commission on Black Deaths in Custody brought down its seminal report, shocking Australia with its account of 99 Aboriginal deaths in police or prison custody over the previous decade – with the causes ranging from neglect to suicide to homicide – little has changed. Julieka’s death has only sparked national outrage because of the callous neglect of those supposed to be caring for her, which was exposed at the Coroner’s inquest.

For Julieka’s uncle, Sean Harris, who has accompanied us to the cemetery, her death was doubly distressing. In 1988, as an 11-year-old boy, his father took him to a demonstration in the Geraldton town centre to protest over the hanging in a police cell of a young local Aboriginal footballer named Edward Cameron.

It turned into a riot as 300 or so angry protesters overwhelmed police, shouting that they were murderers, and smashing every shop window in the main street. It was one of the deaths investigated by the Royal Commission – and yet, says Sean, “Here we are nearly 30 years later and nothing has changed.”

Julieka was “adopted” by her “Nanna” when she was three years old and her mother, Della Roe, separated from her husband and moved away from Geraldton. “It’s not good for a kid to be moving around all over the place… I was happy to have her here with me,” she says.

It was an uneventful childhood in the bustling seaside provincial city 424 kilometres north of Perth, where the large Aboriginal population can still indulge in their traditional pastime of diving for rock lobster off the inshore reefs.

Dark-skinned and slightly-built, when she left school Julieka seems to have fallen in with a bad crowd. In the early hours of November 25 2009 – she was still only 17 – a police patrol found her lying asleep on the roadway near Broome’s famous Cable Beach.

When they woke her up she appeared to be drunk and affected by drugs – “I don’t remember anything after taking that eccy,” she said – and swore at the police.

Carol believes that the real turning point came in 2013 when Julieka started living with a man named Dion Ruffin.

Instead of calling the Kullari Patrol, a local Aboriginal-run service to take her to Broome’s sobering-up facility, they arrested her, charged her with disorderly conduct and failing to give her name and address, and took her to the police station cells for the night. She was bailed to appear in the Children’s Court, but failed to turn up and was fined $200.

No-one is pretending that she wasn’t a wild child. She had two other brushes with the law the following year in the mining town of Port Hedland where she was living, and was charged with disorderly conduct and obstructing and assaulting police – she kicked a policewoman as she was being arrested. Again she was fined.

Bad behaviour, yes. But who would have predicted that five years later those episodes of drunken teenage delinquency would lead to Julieka’s death?

Carol believes that the real turning point came in 2013 when Julieka started living with a man named Dion Ruffin. Ruffin was not only twice Julieka’s age at 42, he was built like a Rugby prop – about 1.90cm tall and weighing 130 kilograms. He had several children by previous partners, and – although Julieka did not know it at the time – he had a criminal record and a nasty history of domestic violence.

Around Christmas that year Della Roe began to worry that Julieka was no longer the “happy go lucky” girl she had known – she had become withdrawn and had lost weight. She confronted Ruffin and said to him “You stole my daughter. I want my daughter back.”

But Ruffin ignored the ultimatum and things began to spiral out of control. Julieka confessed that they were using amphetamines – their fortnightly benefits were gone within a day or two on drugs. Then her family learned that Ruffin was assaulting her.

“Dad, my man flogs me. He broke three of my ribs.”

“Where is the mongrel?”

Around Easter 2014 Julieka came to her grandmother’s house complaining of sore ribs, told her that she was leaving her violent partner, and went home to tell him and to collect her clothes. She returned with a bloody mouth, and Carol told the inquest she asked her,

– Did that dickhead hit you, baby?

– Yes, nan.

Carol testified that she decided that the only way to break the cycle of violence was to get her granddaughter well away from Ruffin. The next day she gave her the bus fare to travel from Geraldton more than 1100 kilometres north to the Pilbara mining town of Karratha, where they had relatives. Julieka planned to enroll for a TAFE course there.

But somehow Ruffin discovered where she had fled for refuge and within a few weeks had enticed Julieka back to live with him in a rented house in nearby South Hedland. The drugs, and the violence, resumed.

In July 2014, a month before her final, fatal encounter with the police, her father Robert Dhu testified that he had this conversation with his daughter:

– Dad, my man flogs me. He broke three of my ribs.

– Where is the mongrel?

When he gave evidence to the inquest, by video-link from his prison cell, Ruffin admitted that he had injured Julieka, but claimed that it happened while they were wrestling after she stabbed him in the leg with a pair of scissors and jumped on his back. “We had a few wrestles and whatnot,” he said. “Julieka had a short temper but, yes, I loved every bit of her.”

No-one gave evidence on who it was that finally dropped the dime on them. But some time on Saturday August 2 someone telephoned the local police to give them Ruffin’s address and inform them that there was an outstanding warrant against him for breaching a domestic violence order taken out by a former partner.

Police arrived at their house around five that afternoon and discovered that not only was Ruffin wanted, but that a “warrant of commitment” for Julieka’s arrest had also been issued three months earlier, for fines relating to her previous brushes with the law. These fines had now, with court costs, jackpotted to $3622.34, and she had been ordered to work them off by serving four days in custody.

Both were arrested, and were taken to the South Hedland police station, where they were put in adjoining cells. Almost from the time she was arrested Julieka was complaining that she was in pain from her previously-broken ribs – the police at first fobbed her off with two Panadol, and then at 8pm that night she was driven to the new Hedland Health Campus, about a kilometer away.

There, after an examination that took only a few minutes, she was given a “triage score” of four – the second-lowest level of medical emergency. The doctor who treated her, Dr Annie Lang, said she was busy, and dismissed Julieka’s pleas for treatment as “behavioural gain … I thought she was being loud to get seen sooner and get pain medication…. I had absolutely no idea she was as sick as she was.” She was given Endone (for pain relief) and diazepam (a mild tranquilizer).

Julieka was back in her cell 45 minutes later, and for the next 20 hours or so was witnessed by several police officers, and by inmates in adjoining cells, to be calling out for help, begging to be taken to hospital, sobbing in agony, and vomiting. When one policewoman asked her to score her degree of pain on a scale of one to ten she replied “Ten.”

Things did not improve when Rick Allen Bond came on duty the following day. When Sgt. Bond, a domineering career police officer with more than 20 years on the force in Western Australia, heard that Julieka was in a bad way he telephoned her father to see if he could bail her out by paying the fine.

He gave evidence that Robert Dhu told him that he did not have “that sort of money,” and that Julieka was “… on drugs. And it wasn’t just cannabis, it was amphetamines or ice.” Sgt. Bond admitted that he formed the view, and told other officers, that Julieka was faking her symptoms “as a ploy to get out of our cells.”

Reluctantly at 4:20pm on the Sunday afternoon, police took her to the medical centre for a second time. She was, said the medical staff, “Crying in pain… tachycardic, grunting, dehydrated and had a pulse rate of 126 beats a minute.” After another brief examination – her temperature was not even taken, because the hospital was short of thermometers – she was dismissed as suffering from drug withdrawal symptoms and sent back to the cells with some paracetemol and another dose of diazepam.

The next morning, when Constable Shelly Burgess arrived at the police station, she says that Sgt. Bond told her: “There’s a girl downstairs… in the lockup. She’s been to hospital twice before. She’s a junkie coming off drugs. She’s faking it now, saying she can’t get up… she’s full of shit.” Bond denied this.

The CCTV footage shown to the court shows Burgess going to the cells, where she tries to yank Julieka into a sitting position, loses her grip and drops her on her head on the concrete floor. When Sgt. Bond arrives, she testified that he bends down to whisper in Julieka’s ear: “You’re a fucking junkie and you’ve been to hospital twice before and this is not fucking on… This is the last fucking time you’re going to hospital.”

Philip Urquhart, counsel assisting the Coroner, asked Sgt. Bond, “Would you say that your treatment of her was inhumane?”

Bond: “I wouldn’t say inhumane. I would say unprofessional.”

By now, Julieka said that she couldn’t feel her body and appeared to be paralysed. She was half dragged, half carried to the police van and driven to the hospital for a third time. When they arrived and she was lifted into a wheel-chair she went limp, her head flopped back and her eyes rolled up. Still police thought she was “faking it.” Said Shelly Burgess: “I thought she was exaggerating and pretending to faint.”

In fact she was having a heart attack. Fifty-three minutes later, at 1:39pm on Monday August 4, resuscitation failed and Julieka was pronounced dead. It was 43 hours after she had been arrested. The post mortem found that she had acute septicemia and pneumonia and died as a result of an “overwhelming staphylococcal infection” which came from an abscess which had formed around her broken ribs.

That was nearly two years ago. So what has happened since, to the three parties involved in Julieka’s death: the police, the medical staff and her abusive partner, Dion Ruffin?

The behaviour of the police speaks for itself, and the WA Coroner, Ros Fogliani, will deliver her findings later this year on whether anyone should be held to account. Julieka’s relatives are not holding their breath, because the Coroner has already refused their request to release the police station videos to the media “so that the whole world can see what happened.”

The family have found the response of the WA Police to their own internal inquiry deeply underwhelming.

Of the officers involved, 11 have received disciplinary letters for failing to follow procedure. The internal investigation found that four of them had “engaged in unprofessional conduct” and their response to Julieka’s deteriorating condition was “…tepid at best…without any sense of urgency … (they) failed to comprehend and respond to the seriousness of the situation.”

But no-one has suffered any financial or career penalty. Two of the officers, in fact, have since been promoted. Sgt. Bond has left the police force to live in Queensland, for “family reasons,” he explained to the inquest.

And when they went to the police station and asked to lay a wreath in the cell where Julieka had lain dying, Carol was near tears as she gave evidence that the police “… said ‘no.’ They said ‘We have to wait for protocol.’ Well, excuse me, did I give them protocol to kill my daughter? Did I?”

Later, after the family tackled the WA Premier, Colin Barnett, they were allowed to visit the police station, where they placed two crosses on the gravelly ground, and planted a desert rose in Julieka’s memory. (Photo above, courtesy Carol Roe)

As for the medical care she received – or, rather, didn’t receive – at the Hedland Health Campus – Carol and Dell and Sean and the rest of Julieka’s extended family will also have to wait to see whether any action is recommended. Expert evidence was given that even as late as her second trip to hospital her life could have been saved if her condition had been correctly diagnosed and she had been given antibiotics.

They have already formed their own views, after listening to the evidence of Sandra Thompson, the Professor of Rural Health at the University of Western Australia.

This is what she told the inquest: “I think that if that had been a white middle-class person there would have been much more effort made to understand what was going on with that person’s pain. So that’s what institutional racism represents.”

Finally, what has become of Dion Ruffin, who inflicted the injuries that led to Julieka’s death? When last heard of in March, he was back in prison serving a sentence for breach of a violence restraining order, burglary, assault and criminal damage. The WA Prisoners’ Review Board revoked his bail, describing him as “a lethal threat to the community.”

Down at the WA Aboriginal Legal Service, in a seedy corner of East Perth, there is also little optimism. I went there to discuss Julieka’s death with its chief executive, Dennis Eggington and the service’s director of legal services, Peter Collins. Both have been fighting for more than 20 years to reform police treatment of Aboriginal people, and to reduce the terrible toll of deaths in custody.

Since Australian tax-payers forked out $40 million for that royal commission 25 years ago things have, if anything, got worse. Before, an average of ten Aboriginal people a year died in custody; in the 19 years to 2008, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (which includes juveniles in its tally) there was an average of 15.

The mean age of death is 50, says the Australian Institute of Criminology, and the overwhelming majority are men. One third of the deaths are from “non-natural causes” which includes suicide. One in five is by hanging – typically using a bed sheet attached to a light fitting, ventilation grille or door-handle, which is doubly reprehensible since one of the most robust recommendations of the royal commission was the removal of these “hanging points” from cells.

It is not that Aboriginal people are more likely to die in custody than non-Aboriginal prisoners; they are not. It is that there are, proportionately so many more of them in Australia’s jails and lock-ups. And Western Australia leads the country, if not the world, in the incarceration of its Indigenous population.

Of the 5743 people in WA prisons at midnight last New Year’s Eve – the macabre moment when the Department of Corrective Services does its annual audit – 38 per cent were Aboriginal, although they only represent 3.8 per cent of the population. Do the maths: Aboriginal people are ten times as likely to be locked up as other people.

And that is just adult men in prison. 48% of the teenagers in juvenile detention are Aboriginal, and at Bandyup Women’s Prison on Perth’s Eastern outskirts the figure is about half, most of them, like Julieka, serving time for not paying fines.

Little wonder former Prime Minister Kevin Rudd marked the seventh anniversary of his historic apology to Indigenous Australia by warning that “Australia is now facing an Indigenous incarceration epidemic.”

Peter Collins says that one of the service’s lawyers was in the remote and notorious East Kimberley town of Hall’s Creek recently and the court list had 120 names on it, of whom 37 were charged with drinking in public. “Aborigines [sic] are the only people charged with that,” he says. “Go down to [Perth’s] City Beach any weekend and you’ll see any number of people having a barbecue and a drink and the police are nowhere to be seen. This really is the Wild West.”

He runs through a list of some of the more bizarrely inconsequential and unnecessary arrests his lawyers have had to deal with:

- 2005, Onslow

A 15-year-old boy jailed for 12 days for attempting to steal an ice-cream. - 2006, Kalgoorlie

An 18-year-old Aboriginal man living in a remote community with a history of mental illness and self-harm. He throws himself in the path of a moving car, cracking the windscreen. Charged with causing criminal damage.

- 2009, Northam

A 12-year-old boy charged with receiving a stolen chocolate Freddo Frog. Mother mixes up the date for his court appearance and the boy is locked up for failing to appear. - 2011, Perth

A 15-year-old intellectually-handicapped boy is charged with receiving a stolen $5 soft toy. Serves three days in jail. - 2011, Meekatharra

An Aboriginal man is stopped in the street by police to be searched. When ordered to remove his socks he flicks then in the face of a police officer and is charged with assault.

“You couldn’t make it up,” he says. “There has got to be an alternative to locking people up for things like this, and for not paying fines.” Which is exactly what the Royal Commission recommended 25 years ago:

Recommendation 87: Arrest people only when no other way exists for dealing with a problem.

Recommendation 92: Imprisonment should be utilised only as a sanction of last resort.

Dennis Eggington is equally pessimistic about reform – although that won’t stop him fighting for it. “I have been here for 20 years and every couple of years you get something like this, some more horrific than others,” he says. There has been a complete neglect of the duty of care and someone needs to be prosecuted or it’s inevitable that there will be another case in the future.”

400 odd kilometres to the North, Carol Roe tends her granddaughter’s grave and makes the same vow. “What we are afraid of is that someone will just get a slap on the wrist and walk away,” she says. “Just another Black death in custody. Well, I can tell you we are not going to allow them to get away with it this time. We are going to fight until we get justice.”

Contact us

Please provide a brief description of your claim.