A Reportable Conduct Scheme (Scheme) began in January 2023, and expanded at the start of this year.

Despite its infancy, Mr Robinson said the reports to the Scheme – which includes significant neglect and emotional and psychological harm to a child, and with a threshold for various types of reportable conduct that differ significantly from a criminal and disciplinary setting – had received 29 notifications of reportable conduct from agencies who administer the youth justice system—all relating to custodial settings.

17 of the notifications concern Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander young people (from government data, not self-identified).

The notifications include 23 allegations of physical assault (including allegations of the use of excessive force); four allegations of sexual misconduct; one allegation of a sexual offence; and one allegation of significant neglect.

Mr Robinson said 15 of the notifications had been closed and 14 are open and currently subject to oversight.

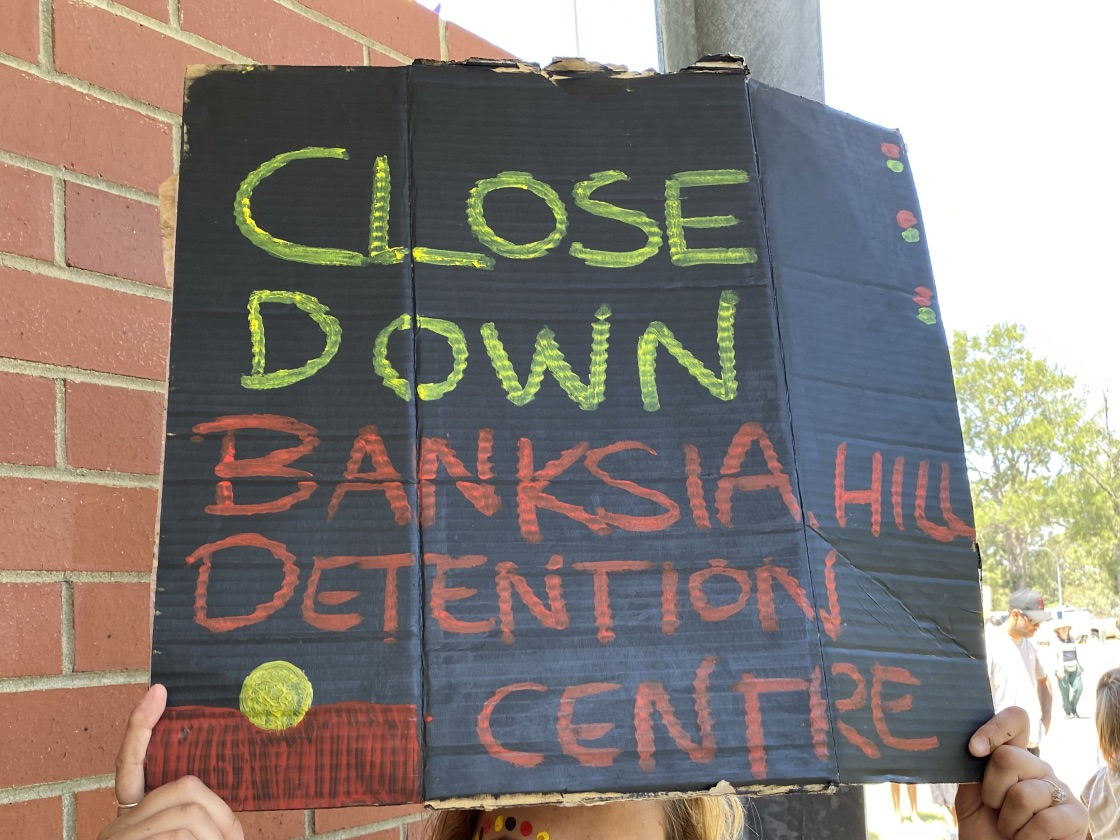

The numbers come as the youth justice system has come under heavy criticism, following the deaths of 16-year-old Yamatji boy Cleveland Dodd last year in Unit 18, and an unnamed 17-year-old teenager in Banksia Hill in August.

The inquest into Cleveland’s death has seen a number of revelations brought forward, including the department lying about having specialist youth justice staff in Unit 18, and children only getting at most, eight hours out of their cells a day—two less than at Banksia Hill.

The longest serving Children’s Court Judge in WA history, Denis Reynolds, told the inquest children being held at Unit 18, were routinely viewed as “inherently bad”.

“At the core of the issue is a false premise,” he told the court.

“In my view, they are vulnerable children. They have neurodevelopmental issues and have loads of trauma.”

The latest Closing the Gap data showed Aboriginal children were incarcerated at almost 35 times the rate of non-Indigenous children in WA.

A report by Commissioner for Children and Young People, Jacqueline McGowan-Jones, found that, despite some improvements, “systemic problems” still remained, and the complex needs of children were not being met at Banksia Hill.

Despite this, Corrective Services Minister Paul Papalia – who has routinely said he can’t comment on the ongoing inquest despite the litany of failures present – said the reason children are spending less time out of their cells at Unit 18 is “because of the cohort and their behaviour”.

“It’s a failure of their behaviour,” he said.

Kurin Minang human rights expert and law academic Dr Hannah McGlade suggested In August Minister Papalia is not fit for the job, arguing “he is not capable of leading reform and he lacks the knowledge and experience – and it is not clear he has the commitment either”.