Coroner in Cleveland Dodd inquest indicates he may call for urgent closure of Unit 18

The coroner probing Western Australia’s first recorded death in youth detention has indicated he may call for the unit where the 16-year-old self-harmed to be closed “as a matter of urgency” as the inquest reaches a major milestone.

WARNING: This story discusses incidents of self-harm and contains the name and image of an Indigenous person who has died.

After sitting for nearly 40 days, the inquest into the death of Cleveland Dodd has finished hearing oral evidence.

The teenager had been detained in Unit 18, a maximum-security adult prison unit hastily turned into a youth detention facility in mid-2022.

Coroner Philip Urquhart on Wednesday handed down 18 “preliminary recommendations” which he may make as part of his ultimate findings late next year.

Chief among them is that “Unit 18 should be closed as a matter of urgency”, given it was only ever meant to be a temporary facility.

He added that if Unit 18 was to remain open for the foreseeable future – as the government has indicated will be the case – a new way of running it, known as a model of care, must be implemented “as a matter of urgency”, detainees should only be sent there for a maximum of six weeks and they should be allowed longer meetings with lawyers.

Lawyers involved in the case will return to court in mid-June to make closing submissions before the Coroner prepares his final findings and recommendations.

‘Child of the sunrise’

The final piece of oral evidence received by the court was a statement from Cleveland’s mum, read to the court by a friend.

Nadene Dodd, who has travelled from her home in Kalgoorlie to attend much of the inquest, was too emotional to address the court.

Her words gave some of the first insights into who Cleveland Dodd was as a person, before he died a week after self-harming inside his cell.

Ms Dodd described her “child of the sunrise, of sweeping deserts and untampered earth” returning to the earth after living just a fifth of his life, saying his loss “will be with me wherever I go, for as long as I live”.

“Cleveland was denied the opportunity to realise his potential,” the court was told, as a photo of the 16-year-old she said has “limitless” compassion and kindness was displayed on screens.

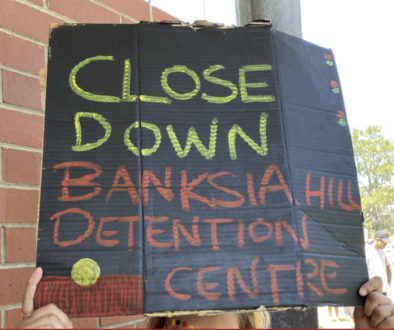

“I know he would have been a great and noble man, who would have achieved great things, who would have overcome the challenges [and] battles that led him to the horrible concrete jungle of Banksia Hill and then to the hellhole of Unit 18 where he grew so desperate that he took his own life.”

The statement described images of Cleveland “surrounded by uneaten plates of food” which “cannot be unseen”, describing the cell where he took his last breath as “barren and filthy”.

“Institutional abuse of children is unacceptable, in the same way that any abuse of children is unacceptable. We should hold governments to a higher, not a lower standard,” Ms Dodd said.

It emerged during the inquest that of his final stint in detention, he was locked in his cell for more than 22 hours a day — the United Nations’ definition of solitary confinement — for more than 80 per cent of those 93 days.

“He was a talented artist who loved painting and drawing, he could rise horses bareback and he loved all animals. He loved playing sports, and his favourite was basketball,” Ms Dodd said.

“It breaks my heart to know that from the moment he was transferred to Unit 18, Cleveland never got the chance to go outside, to feel the sun on his skin, to breathe in fresh air, to look at the sky.”

The Director General of the Justice Department at the time, Adam Tomison, admitted on the stand some young people had been subjected to “institutional abuse” and that a document provided to the minister to approve opening the unit contained “blatant lies”.

Unit ‘set up to fail’

Those were just two of many stunning admissions Coroner Philip Urquhart has heard across 39 days of hearings spread through the year.

Staff told the inquest the unit was “set up to fail” and a “war zone” where it was impossible to keep young people safe.

A litany of systemic failures meant Cleveland was not observed through CCTV as he should have been, leaving 13 minutes between the last time he was checked after threatening to take his life and resuscitation efforts beginning.

The probe has extended well beyond the events of that night though, going as far back as 2009 at one point, as Coroner Urquhart tried to understand how the Department of Justice came to create Unit 18, what failures occurred in that process, and what needs to change to avoid another tragedy.

His findings are not expected until mid-to-late next year after hearing from lawyers about what conclusions he should reach.

In her statement, Ms Dodd vowed regardless of the inquest outcome she would be a “stalwart to change, to a kinder world” and that her son’s death would not be in vain.

“The time has come for those responsible for the administration of youth justice to be held to account,” Ms Dodd’s statement read.

“I hope that this process, which is unambiguously difficult for me and my family, and indeed all those who loved Cleveland, will be the catalyst for real and lasting change.

“My son didn’t deserve to be treated the way that he was treated.

Corrective Services Minister Paul Papalia declined to comment on the recommendations, saying the inquest was ongoing.

A spokesperson referred to previous comments the minister had made about improved conditions in detention, increased out-of-cell hours and increased recruitment.

Contact us

Please provide a brief description of your claim.