WA Justice ‘incompetent and incapable’: Former Children’s Court judge

Key points:

-

Denis Reynolds gave evidence on day three of a protracted inquest into the Indigenous teenager’s death last October.

- Reynolds has publicly spoken out about the conditions at the unit since he retired.

- He also called the department “incompetent” and “incapable” of change and called for an external group to oversee changes made to youth detention.

Warning: This story carries the name and image of a deceased Indigenous person, with his family’s permission.

A former Children’s Court judge said he predicted there would be a death at Unit 18 a year before 16-year-old Cleveland Dodd was found unresponsive in his cell, later dying from his self-inflicted injuries.

Denis Reynolds, who was Children’s Court president from 2004-2018 before he retired, gave evidence on day three of a protracted inquest into the Indigenous teenager’s death last October.

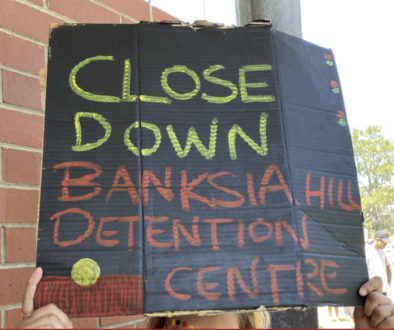

Dodd was being held at the notorious Unit 18, a section of Casuarina’s adult prison created specifically for difficult-to-handle children and youths overflowing from the main children’s prison Banksia Hill.

Reynolds has publicly spoken out about the conditions at the unit since he retired, and on Wednesday further slammed the department that oversaw the handling of youth detention in WA, as well as politicians including former premier Mark McGowan and former corrective services minister Bill Johnston for “demonising” the troubled youths Unit 18 housed.

“You have heard the former premier describe these children as terrorists,” he told the inquest.

“Saying things like Banksia’s got rapists and murderers – elevating them to the point where the public will think these children are terrible and the treatment they’re getting there is justified.”

Reynolds said he had raised concerns about Banksia Hill as long ago as 2013 and said the Department of Justice had met with repeated resistance his requests for detailed detention management reports about conditions at the centre.

“You wanted to know about their recreational opportunities, visits, education, were they subject of restraints, so the court could inform themselves,” he said.

“The department was actively trying to dissuade that process.”

Reynolds added that while he “firmly believed” some structural changes desperately needed to be made to the way children who committed criminal offences were handled in WA, he also spoke passionately about a much-needed attitude shift.

“A false premise is that the children that have been sent to Banksia and subsequently Unit 18 … are inherently bad … the children we’re talking about are vulnerable children. The most vulnerable children in our community.”

“I think at the core of the issue is a false premise,” he said.

“A false premise is that the children that have been sent to Banksia and subsequently Unit 18, that the children are inherently bad. That their behaviour such as threatening staff and assaults … is the product of children being inherently bad. Whereas my firm view is that the children we’re talking about are vulnerable children. The most vulnerable children in our community.

Reynolds’ recommendations for change included regional detention centres divided into smaller age and gender groups so that the children could remain close to family, a recommendation that the former inspector of custodial services has also given the inquest.

He added that besides the benefit to the children and families involved and to the system’s effectiveness, this would save $20,000 upfront in flying each child from the far north of WA to Perth.

He also said it was “essential” a department be set up to manage the handling of young offenders in prisons given that there were currently 7000 adult prisoners and 65 child prisoners.

“If you’ve got a department weighted like that, it’s overwhelmingly concerned with adults,” he said.

“Children are very different. They’re not small adults.”

Reynolds said the aim should be for children to leave detention “better equipped” with skills that made them function better in the community upon leaving, but claimed that was currently vanishingly rare.

He also called the department “incompetent” and “incapable” of change and called for an external group to oversee changes made to youth detention because the department couldn’t be trusted to do it themselves.

“That’s why you’ve got a young person who committed suicide despite constant warnings,” he said.

Reynolds reiterated that he believed rehabilitation must have “a therapeutic approach” as its primary focus for children who offended.

He said politicians were peddling a lie that they were keeping the community safe by locking up children in a prison environment, as re-offending rates painted a vastly different picture.

“A vulnerable child emerges from a detention or prison-type environment worse than when they went in,” he said.

Reynolds spoke directly to Cleveland Dodd’s family, who have attended every day of the inquest and offered his “sincere apologies” for their suffering.

“The death of a child is always unbearable,” he said.

He added that Cleveland’s death was “preventable, predictable and predicted”.

“[There needs to be] accountability for it,” he said.

“Recognition of it by the state and immediate systemic changes made of the law and humane treatment of children in care.”

Contact us

Please provide a brief description of your claim.