Filthy and overrun with rats: Banksia Hill detention centre in ‘acute crisis’, inspector finds

A damning inspector report into the troubled Banksia Hill detention facility has found “every element” of the centre is failing, with “young people, staff and a physical environment in acute crisis”.

A damning inspector report into the troubled Banksia Hill detention facility has found “every element” of the centre is failing, with “young people, staff and a physical environment in acute crisis”.

The report from the Inspector of Custodial Services, Eamon Ryan, was released on Thursday, but was provided to the Western Australia parliament on 8 May, one day before to the most recent riot at the detention centre. Inspections were carried out in early February 2023.

The riot at the juvenile facility for offenders aged 10-17 years, lasted two days as dozens of the approximately 90 youths detained at the facility allegedly burned buildings, threatened staff and attempted to escape.

The safety of the detention centre has long been criticised, with Western Australia’s Aboriginal Legal Service (ALSWA) labelling the treatment of children in the facility as “child abuse”.

Ryan’s team included specialist advisers on education, health, mental health and cultural safety, and found the centre to be in a state of emergency.

“Every element of Banksia Hill was failing, often through no fault of its own or the efforts of staff,” he said. “Ultimately, we saw young people, staff and a physical environment in acute crisis.”

Ryan said there were site-wide confinement orders in place at the centre for every day of the 10-day inspection, meaning young people were locked in cells “for excessive lengths of time in order to maintain the good government, good order and security of the centre” which he said was due to a lack of sufficient staffing.

He said the daily staff shortages were unprecedented, the staff attrition unsustainable and recruitment was not able to keep pace.

He said keeping young people locked in cells causes a self-perpetuating cycle at the centre, with the isolation increasing anxieties, anger and frustration, which can sometimes lead to acting out negatively.

“The help these young people need and the effective rehabilitation they require are exactly the types of interventions (education, programs, recreation, training, family reconnection and general health and mental health) that have been most heavily impacted by staffing shortages and increased lockdowns,” he said.

The report quotes youth saying that being kept in cells for long periods of time made them feel suicidal, depressed and alone. During the 10 days of inspection, there were less than 30 custodial staff available for each day shift, and the weekend before the inspection, the centre ran with just 15 officers on one day, and 16 the next.

On that weekend, the lack of staff meant young people from the good behaviour unit were employed to serve meals to others in the centre.

The report notes the current staff-to-young-people ratio at 1:8 is “unsafe”.

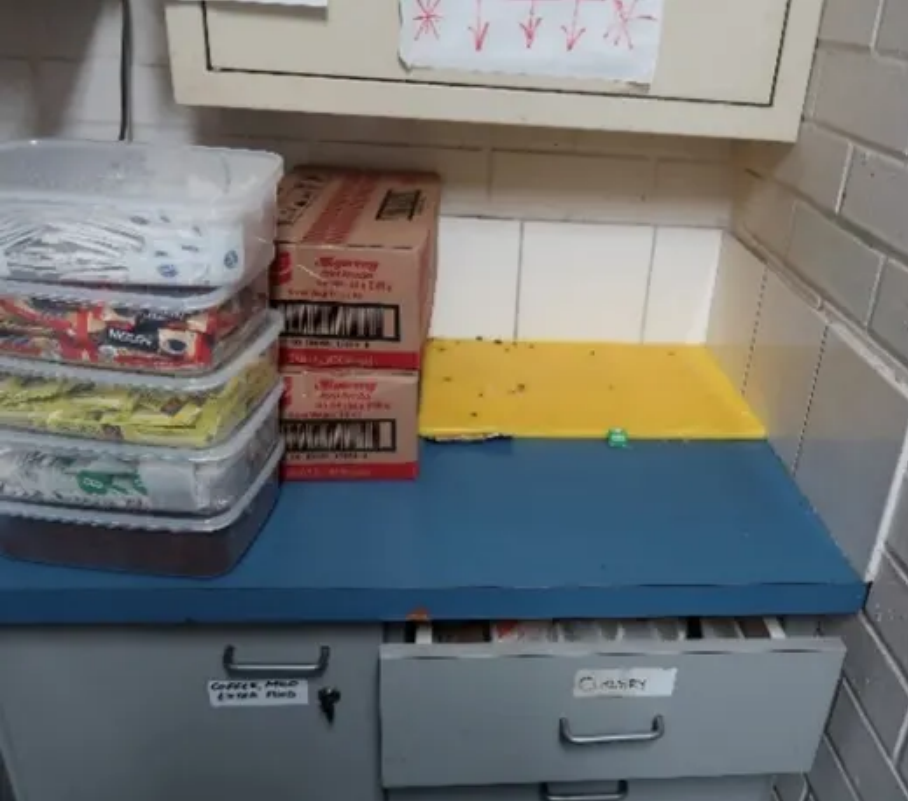

The inspection also found the centre in a general state of disrepair, with food left to rot in cells, piles of dirty laundry and rubbish and a rat infestation with “tens of rats” observed after a lockdown one evening.

Ryan said the riots on 9 and 10 May were an “enormous setback” for the centre, and the situation will need to be monitored in the weeks and months to come.

Ryan’s findings echo the comments of relatives of those detained in the centre. Lee-Anne Mason told Guardian Australia in May that she was alarmed at the treatment of Indigenous youth at the centre.

Among the 10 recommendations in the report, Ryan called for the WA government to commit to a second youth detention facility, stating Banksia Hill does not work, and the use of Casuarina prison’s Unit 18 where young people are sometimes kept, demonstrates the “need for a smaller facility for those with complex behavioural needs”.

The other recommendations include improving recruitment, staff retention, and urgently recruiting Indigenous-related positions, setting tight timeframes for hearings for those being detained in the centre, and setting up more support roles.

The WA department of justice accepted most recommendations, but said a decision on a new facility was a matter for government, and rejected a recommendation for an alternative location for a crisis support centre, noting it would require a significant redesign of the facility.

The department acknowledged staffing issues had caused difficulties.

“The complex behaviours of some young people have resulted in staff assaults and contributed to increased workers compensation and personal leave,” the department said.

“The current national labour market and media reports of incidents have made attraction and retention of staff even more difficult. Regrettably, this has a flow on effect on the provision of services to detainees.”

The inspector’s report is in two parts, the first focusing on the immediate issues at the centre, and a second to be released in the coming months focused on the welfare and support for young people at the centre.