What is FASD and how much of a role did it play in the latest Banksia Hill Detention Centre riot?

Key points:

-

For the last week, the WA premier has been locked in a bitter and impassioned battle even another massive budget surplus couldn’t distract from.

-

But while the premier has spent the week talking about the need for “tough love” and consequences, health professionals and advocates have argued that won’t work.

-

The Department of Justice said diagnosing things like FASD required “specialised multi-disciplinary assessment”, with reports usually requested by a court.

For the last week, the WA premier has been locked in a bitter and impassioned battle even another massive budget surplus couldn’t distract from.

At the centre of it were four words he uttered in a Bicton bakery last Wednesday, as he vented about the latest riot at Banksia Hill Juvenile Detention Centre.

“That’s more excuse making,” he said.

The premier had just been asked about the consequences conditions like foetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) and other neurological disabilities could have on the types of kids that end up in youth detention.

Few, if any, would argue that their behaviour in lighting fires and damaging buildings was anything but unacceptable.

But while the premier has spent the week talking about the need for “tough love” and consequences, health professionals and advocates have argued that won’t work.

Not because they see things like FASD as an excuse, but because it means young people are often physically unable to understand the consequences authorities are trying to impose, and as a result, won’t change.

What conditions do these young people have?

The best information we have is that around nine out of every 10 have at least one form of severe brain impairment, which is likely to lead to problems with the law.

That was one of the key findings of landmark research by the Telethon Kids’ Institute, published in 2018, that assessed 99 young people at Banksia Hill.

Some of the biggest issues were with:

- Academic achievement (62 per cent) including reading, writing, spelling and maths

- Attention (55 per cent) which can lead to hyperactivity or being easily distracted

- Executive function (54 per cent) which causes problems with understanding consequences and learning from mistakes

- Language (45 per cent) leading to people not understanding instructions or what they are agreeing to.

Just over one-third of young people who took part in the study were diagnosed with FASD, a neurodisability caused by exposure to alcohol before birth.

“It can affect the way that they remember things, the way that they learn, the way that they communicate and understand social rules or expectations of what’s happening around them and the way they understand cause and effect, or consequences of their actions,” one of the Telethon researchers, Hayley Passmore, said.

Of those who did not have FASD, 84 per cent had at least one other kind of severe mental impairment.

How does this relate to last week’s riot?

Last Wednesday night at Banksia Hill, as the riot broke out, 15 of the 87 detainees had been diagnosed with FASD.

YouTube: FASD screening

Nine of them were at Banksia Hill on remand, meaning they were yet to be sentenced.

Of the 47 detainees who participated in the riot, 11 had been diagnosed with the disorder, according to an answer given to Liberal MP Peter Collier in parliament yesterday.

But the true number was almost certainly higher given low testing and assessment rates.

The Department of Justice said diagnosing things like FASD required “specialised multi-disciplinary assessment”, with reports usually requested by a court.

“That report can then be utilised by the Department of Justice to assist with management of a young person in detention,” a spokesperson said.

What else did the premier say?

Since his comment last week, the premier has continued to be asked about his stance on Banksia Hill and the disabilities that detainees there have.

“It makes things more understandable but it doesn’t excuse things,” he said on Friday when asked about FASD.

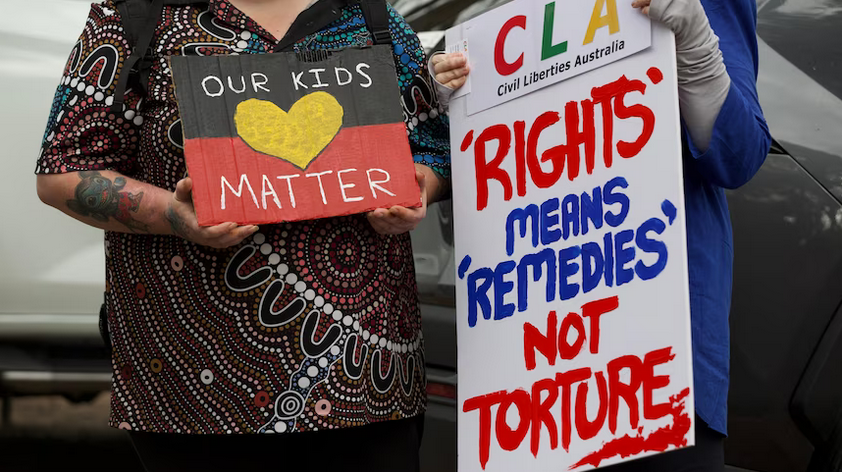

Mr McGowan took a similar line on Sunday, ahead of a rally outside Banksia Hill.

“We need to actually hold people to account for what they do and the juveniles need to get the message,” he said.

“The more you say that no one’s responsible for their actions and there’s no consequences, the more this behaviour will continue.”

Is FASD an excuse?

But few, if any, are suggesting there shouldn’t be consequences for young people who do the wrong thing, despite the premier’s comments.

Dr Passmore, who now lectures in criminology at the University of Western Australia’s law school, said the issue was not with the idea of consequences, but instead the type of consequences and making sure they made sense to detainees.

That’s because about half of the group tested as part of the Telethon study had severe impairments in being able to understand cause and effect.

“They need consequences that will be immediate,” Dr Passmore said.

“If a behaviour or an incident happens in the morning, they might need a response that happens immediately, rather than something that might occur at the end of the night like early lockdown or loss of TV during that night.”

That effect is only magnified for some young people, when going into detention is used as punishment for a crime they committed months, or even years, earlier.

“That’s not going to be practical for a young person who might misunderstand or not be able to comprehend those consequences.”

What’s the solution then?

In practical terms, that means a few things need to be done differently.

First, Dr Passmore said, young people need to have their needs identified as soon as possible so that individual plans can be drawn up by professionals – like speech pathologists and psychologists – to help staff manage the young people in their care.

She said it was important for those plans to look at how positive behaviour could be rewarded, instead of just punishing bad behaviour.

“It could be something as simple as … working towards a privilege that they really aspire to, like have their own clothes inside or their own shoes inside,” Dr Passmore said.

“Something that is meaningful for them, and that gives them a reward or a privilege that they want access to.

“Then, if they had a support plan in place and supervision to be able to meet that support plan, they can take small steps to working towards those goals.”

How are FASD detainees treated?

In response to questions from the ABC, the department said once a detainee is diagnosed with a neurological disability the Youth Justice Psychological Services team “develops and disseminates to staff an individual engagement plan”.

They said staff are currently required to consider a range of factors in deciding suitable consequences for detainees, including:

- Age, gender and background

- Disability and other cognitive needs

- Diversity and cultural and religious beliefs.

A team also provides individual interventions to address young people’s offending.

“These take into account a detainee’s capacity to engage, through such factors as intellectual and/or cognitive impairment, attentional difficulties or neurodevelopmental issues,” the department said.

How does that work day-to-day?

The second part is training staff, and particularly youth custodial officers, to understand how they need to adapt what they do so it can be understood by young people with cognitive impairments.

“When those frontline officers are able to learn about what it’s like for these young people living with a neurodisability, then they are better equipped to be able to understand what the young person’s needs might be, empathise and be able to respond appropriately,” Dr Passmore said.

“We know that these frontline staff want access to this information and when they get it in a way that is meaningful and practical for their job, they’re able to then apply it.”

Those changes could be as simple as using visual aids to help young people understand an instruction, or repeating information in short, simple sentences.

Dr Passmore is part of a group that had been providing training to guards at Banksia Hill and other youth detention centres across the country to help them do just that.

The ABC understands the training has not been run for staff at Banksia Hill since late last year.

The department said officers’ training included working with young people with a disability.

What does the government say?

The WA government is implementing a new way of running Banksia Hill with a “trauma-informed, therapeutic approach”.

The Department of Justice declined the ABC’s request to interview former mental health commissioner Tim Marney, who is leading that work, to understand more about what will change at the facility.

“Implementation will include an increase in specialist staff and allied health professionals, such as speech pathologists and occupational therapists,” the department said.

“This would supplement the supports and interventions already available for young people with neurodisabilities or neurocognitive impairments.

“The model also encompasses an increase in operational staff, providing enhanced capacity for intensive support and monitoring.”

Mr McGowan and Corrective Services Minister Bill Johnston insist that on top of that, the government is doing everything it can to keep young people out of Banksia Hill, while also investing $105 million to improve facilities and programs there.

“I accept that FASD leads to challenges in managing the detainees,” Mr Johnston told parliament yesterday.

“And if the courts don’t think that those people suffering FASD should come to Banksia Hill then I would welcome that.

“That’s why we’re investing in an on-country facility in the Kimberley, an Aboriginal-led solution to some of the challenges for juvenile justice.”

While those plans have been welcomed, major flooding in the region has caused problems, with the government now having to look for an alternative site after one was chosen earlier this year.

Mr Johnston said the government was also investing millions into programs like Target 120 to stop children ending up in juvenile detention in the first place.