Boy, 15, in solitary for 79 days

Originally published on The Australian written by Paige Taylor

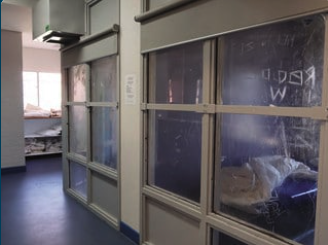

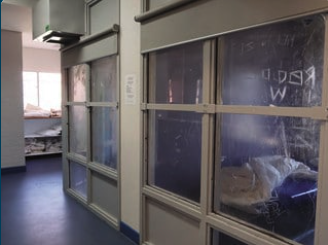

A 15-year-old boy was locked alone in a glass-walled observation cell for 79 days, including Christmas Day, and on just 34 of those days he was led from solitary confinement to a 20m-long cage where he was permitted to exercise for about one hour.

Perth Children’s Court president Hylton Quail on Thursday described the boy’s treatment at Banksia Hill Juvenile Detention Centre as illegal and a case of “prolonged, systemic dehumanisation and deprivation”.

On 33 of the 79 days in solitary confinement – including from December 24 to 28, 2021 – the boy did not get to leave his cell for any reason.

The boy pleaded guilty to assaulting guards 19 times while at Banksia Hill, including by spitting, biting, punching and kicking them.However, Judge Quail released him on Thursday to live with his grandmother.

“When you treat a damaged child like an animal they will behave like one, and if you want to make a monster this is how you do it,” JudgeQuail said.

Evidence at the boy’s sentencing hearing on Thursday included a guards’ logbook of the boy’s time in solitary confinement that is likely to bolster a class action against the McGowan government by current and former inmates of Banksia Hill. Most of the young people who have joined the court case are Indigenous, and so are most of the current detainees at the centre.

The logbook documents the consequences of chronic understaffing at the centre. It reveals that on many days there were not enough workers in the Intensive Supervision Unit where the boy was held. The unit was so understaffed that there was often no guards available to escort detainees to the phone room to call family or to the caged exercise yard.

“(The boy)’s experience of detention at Banksia Hill has been one of prolonged, systematic dehumanisation and deprivation. It has had no rehabilitative element or effect and has been unjustly punitive,” Judge Quail said. “The conditions of his detention have not met the bare minimum standards the law requires.”

The Aboriginal boy has been a ward of the state since he was seven. The court heard that when he lived with extended family in his earliest years, he was beaten and witnessed domestic violence against others.

He was exposed to substance abuse and what Judge Quail called “normalised criminal behaviour”.

He was 11 when he met his mother, who had substance abuse issues. The boy’s father died of alcoholism when he was eight. The boy was traumatised but “did pretty well” between the ages of nine and 12 when he lived in a group home run by the state government department now called Communities, Judge Quail said in his sentencing remarks.

However, when he was too old for his group home, he began to get into trouble. He has been in and out of Banksia Hill since 2019, mostly for burglaries. He has been diagnosed with foetal alcohol spectrum disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, ADHD and a general anxiety disorder.

“He is one of the most damaged children to have appeared before me,” Judge Quail said.

The court heard the boy was arrested and sent to Banksia Hill on November 5, 2021, because he broke into a house and stole clothes and a carton of cigarettes. Though none of his crimes in the community involved physical attacks on people, he lashed out at guards with ferocity and sometimes more than once a day.

In a report to the court, a detention centre psychologist who had a rapport with the boy described him as polite, responsive and respectful at their meetings. However, he was also impulsive with a fear of abandonment and had “little regard for his life when highly stressed”.

The report said he responded to the isolation and boredom of repeated 24-hour lockdowns in his cell by “trying desperately for any interaction with staff, even a negative one”.

He threw cups of his urine at passing guards through a small window in his cell door. He repeatedly bashed his own head against the cell walls until guards restrained him. On one of the occasions when the boy was self-harming, riot squad officers from a nearby maximum-security adult prison arrived to prevent him from taking his life.

While confinement orders allow children to be held in special handling cells in Western Australia, the child must have 9.6 hours of exercise a day with fresh air and the company of youth custodial officers. The most time the boy ever got in the exercise “cage” was about three hours when he got into a standoff with guards.

Judge Quail said there was no confinement order for the boy that authorised his time in solitary confinement. The detention centre management held him there for 79 days on the strength of a document they wrote themselves called “a personal support plan”.

Boy, 15, in solitary for 79 days

Originally published on The Australian written by Paige Taylor

A 15-year-old boy was locked alone in a glass-walled observation cell for 79 days, including Christmas Day, and on just 34 of those days he was led from solitary confinement to a 20m-long cage where he was permitted to exercise for about one hour.

Perth Children’s Court president Hylton Quail on Thursday described the boy’s treatment at Banksia Hill Juvenile Detention Centre as illegal and a case of “prolonged, systemic dehumanisation and deprivation”.

On 33 of the 79 days in solitary confinement – including from December 24 to 28, 2021 – the boy did not get to leave his cell for any reason.

The boy pleaded guilty to assaulting guards 19 times while at Banksia Hill, including by spitting, biting, punching and kicking them.However, Judge Quail released him on Thursday to live with his grandmother.

“When you treat a damaged child like an animal they will behave like one, and if you want to make a monster this is how you do it,” JudgeQuail said.

Evidence at the boy’s sentencing hearing on Thursday included a guards’ logbook of the boy’s time in solitary confinement that is likely to bolster a class action against the McGowan government by current and former inmates of Banksia Hill. Most of the young people who have joined the court case are Indigenous, and so are most of the current detainees at the centre.

The logbook documents the consequences of chronic understaffing at the centre. It reveals that on many days there were not enough workers in the Intensive Supervision Unit where the boy was held. The unit was so understaffed that there was often no guards available to escort detainees to the phone room to call family or to the caged exercise yard.

“(The boy)’s experience of detention at Banksia Hill has been one of prolonged, systematic dehumanisation and deprivation. It has had no rehabilitative element or effect and has been unjustly punitive,” Judge Quail said. “The conditions of his detention have not met the bare minimum standards the law requires.”

The Aboriginal boy has been a ward of the state since he was seven. The court heard that when he lived with extended family in his earliest years, he was beaten and witnessed domestic violence against others.

He was exposed to substance abuse and what Judge Quail called “normalised criminal behaviour”.

He was 11 when he met his mother, who had substance abuse issues. The boy’s father died of alcoholism when he was eight. The boy was traumatised but “did pretty well” between the ages of nine and 12 when he lived in a group home run by the state government department now called Communities, Judge Quail said in his sentencing remarks.

However, when he was too old for his group home, he began to get into trouble. He has been in and out of Banksia Hill since 2019, mostly for burglaries. He has been diagnosed with foetal alcohol spectrum disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, ADHD and a general anxiety disorder.

“He is one of the most damaged children to have appeared before me,” Judge Quail said.

The court heard the boy was arrested and sent to Banksia Hill on November 5, 2021, because he broke into a house and stole clothes and a carton of cigarettes. Though none of his crimes in the community involved physical attacks on people, he lashed out at guards with ferocity and sometimes more than once a day.

In a report to the court, a detention centre psychologist who had a rapport with the boy described him as polite, responsive and respectful at their meetings. However, he was also impulsive with a fear of abandonment and had “little regard for his life when highly stressed”.

The report said he responded to the isolation and boredom of repeated 24-hour lockdowns in his cell by “trying desperately for any interaction with staff, even a negative one”.

He threw cups of his urine at passing guards through a small window in his cell door. He repeatedly bashed his own head against the cell walls until guards restrained him. On one of the occasions when the boy was self-harming, riot squad officers from a nearby maximum-security adult prison arrived to prevent him from taking his life.

While confinement orders allow children to be held in special handling cells in Western Australia, the child must have 9.6 hours of exercise a day with fresh air and the company of youth custodial officers. The most time the boy ever got in the exercise “cage” was about three hours when he got into a standoff with guards.

Judge Quail said there was no confinement order for the boy that authorised his time in solitary confinement. The detention centre management held him there for 79 days on the strength of a document they wrote themselves called “a personal support plan”.