The Detention of Indigenous Youth is a Scourge on Australia

Detention in Australia

Throughout Australia, the age of Criminal Responsibility is set at just ten years of age. As such, “youth offenders” or “young people in detention” refers to individuals aged between 10 and 17 – a significant age gap given the difference in development, both physically and mentally, between a 17 year-old and a 10 year-old. In contrast, the global median age for criminal responsibility is 14.[1] There are two guiding principles upon which the Australian youth justice system is based, and which are incorporated in state and territory legislation. First, young people should be detained only as a last resort and secondly, this detention should only be for the shortest appropriate period.[2]

Australia has also ratified the following conventions, all of which pertain to the manner and circumstances in which youth are detained:

- the United NationsConvention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC)

- the Standard Minimum Rules for the Administration of Juvenile Justice (“the Beijing Rules”) 1985.

- the United Nations Guidelines for the Prevention of Juvenile Delinquency (“Riyadh Guidelines”) 1990.

- the United Nations Rules for the Protection of Juveniles Deprived of their Liberty

- the Optional Protocol to the Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment(OPCAT), 2017.

OPCAT requires Australia to monitor the rights of people deprived of liberty, including children in detention and aims to improve how people’s human rights are protected when they are detained. It does this by providing for a rigorous process of independent inspections of all places of detention in a country’s jurisdiction. In so doing, OPCAT enables a light to be shone on the conditions experienced by people in detention.

Youth Crime and Stakeholder Resistance

Stakeholders for Indigenous youth crime include: Indigenous youth offenders, their victims, the affected community and juvenile justice professionals.[3]

Each stakeholder “exerts a distinctive influence on the development of legal policy that aligns with their existing interests, either consciously or implicitly. The interplay of their diverse, often contradictory, reactions to regulatory change will collectively alter how the reforms transpire and can distort or undermine strived-for change.”[4]

[1] Heather McNeill. “Fears WA youth justice system is broken”. (Western Australia Today, January 22, 2019).

[2] Australia Institute of Health and Welfare. Bulletin 148, 2020, pp3.

[3] Sarah Xin Yi Chua and Tony Foley. “Implementing Restorative Justice to Address Indigenous Youth Recidivism and Over-Incarceration in the Act: Navigating Law Reform Dynamics.” Australian Indigenous Law Review, Vol 18. No. 1 (2014/2015), pp138.

[4] Sarah Xin Yi Chua and Tony Foley. “Implementing Restorative Justice to Address Indigenous Youth Recidivism and Over-Incarceration in the Act: Navigating Law Reform Dynamics.” Australian Indigenous Law Review, Vol 18. No. 1 (2014/2015), pp141.

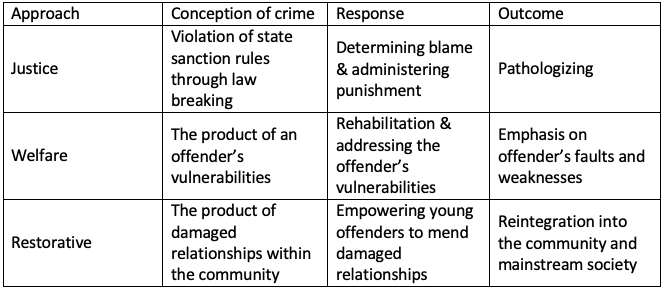

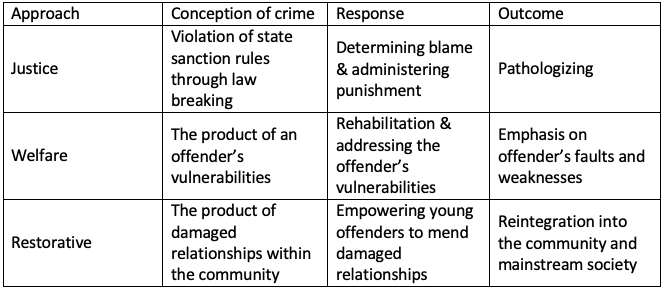

The Three Main Approaches to Youth Crime

Restorative justice is a process where all parties with a stake in a particular offence come together to resolve collectively how to deal with the aftermath of the offence and its implications for the future.

Restorative justice depends upon a law reform strategy that:

- Addresses underlying colonial or racialized manner in which law reform is implemented; and

- Overcomes the tensions that exist between stakeholders about how the law should work in practice.

The Over-representation of Indigenous Youth in Detention

Although less than 5% of youth in Australia are Indigenous, they account for more than half of all youth detained in Australia.

In the June quarter 2019, young Indigenous Australians aged 10–17 were 21 times as likely as their non-Indigenous counterparts to be in detention on any average night.

- 57% of juveniles in detention in the June quarter 2019 were Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander though they made up just 6% of the Australian population aged 10–17

The Productivity Commission’s Report on Government Services of 2019 revealed that “Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youths in 2017-18 were nationally 24 times more likely to receive detention-based supervision than a non-Indigenous child.”

Cost of Indigenous Over-representation Generally

“It is estimated that the “total justice system costs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander incarceration in 2016 were $3.9 billion.”

When the costs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander incarceration are broadened beyond those directly related to the justice system to include things such as: the loss of productive output during incarceration, the cost of crime incurred by victims, the cost of increased mortality, excess burden of tax, and welfare costs, the costs of incarceration rise to $7.9 billion.

“As well as the cost of imprisonment to the State, imprisonment has immediate and ongoing financial and social costs for both the imprisoned person and their family.” (ALRC 2018), which can then project the underlying socioeconomic factors which are the greatest predictors of criminality to the next generation.

Indigenous Youth Re-offending Rates Remain Consistently High

“Aboriginal prisoners tended to be younger, have a higher security rating, and have a substance abuse problem, the analysis indicated that even after all these risk factors were accounted for, Aboriginal prisoners still reoffended at a greater rate compared to non-Aboriginal prisoners. These enduring differences are likely due to other social disadvantage risk factors that were not included in the analysis.” (OICS 2014)

Reasons for Indigenous Overrepresentation

- Colonial or racialized attitudes toward the implementation of reform which persist. Penal policies have been closely tied to imperialist and colonialist strategies which legitimated, and normalised, discriminatory penal practices toward Indigenous groups;

- Systemic bias in the operation of Australia’s laws;

- The discriminatory nature of policing in Indigenous communities and the criminalisation of Indigenous youth in Australia is widely acknowledged and continues to be a major obstacle to the legitimisation of mainstream legal policies.

- A ‘one-size-fits-all’ approachto crime prevention, rehabilitation and punishment, which remains committed to a mainstream criminal justice approach.

Indigenous Youth Suicide Rates

Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander suicides comprise 6% of Australia’s total suicides. Shockingly, however, 80% of child suicides aged 12 and below are by Aboriginal children. For the past decade, nearly 30% of the child suicides to age 17 were comprised of Indigenous children.[1]

While correlation does not necessarily equal causation, it is hard to ignore the link between the high percentage of First Nation youth suicides and the high incarceration rates given that youth who have been incarcerated are at a greater risk of developing depression and attempting suicide or self-harm. Incarceration also contributes to a break down in relationships and lower levels of education (The Conversation).

Western Australia – Australia’s Worst for Rates of Indigenous Incarceration

According to the most recent available census data, the population in Western Australia (WA) is just shy of 2.5 million. Of this 2.5 million, people of First Nations heritage account for only 3.1% of the population (Australian Bureau of Statistics).

WA imprisons Aboriginal people at a higher rate than any other state or territory, with 4.1% of its Aboriginal population behind bars, compared to 2.9% in the Northern Territory and a national rate of 2.6%.

Despite accounting for such a small part of the population, recent statistics supplied by the Department of Justice in WA show that within the adult prison population almost 40% of prisoners are of First Nations people (WA DOJ Adult Prisoners). The situation is even more disproportionate where youth offenders are concerned; over two-thirds (68.67% to be specific) of young people in custody in WA are First Nation people (WA DOJ Youth Detainees).

Reasons for Indigenous Over-representation in Western Australia

The Productivity Commission’s Report on Government Services of January 2019 revealed WA was one of only two jurisdictions nationwide to reduce funding to its youth justice services between 2016-17 and 2017-18, cutting $1.2 million from its detention and diversion programs, and community-based orders and services.

Funding cuts are also at odds with the Australian Law Reform Commission’s recommendations that “Commonwealth, state and territory governments should support justice reinvestment trials initiated in partnership with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, including through:

- facilitating access to localised data related to criminal justice and other relevant government service provision, and associated costs;

- supporting local justice reinvestment initiatives; and

- facilitating participation by, and coordination between, relevant government departments and agencies.”(ALRC “Pathway to Justice Inquiry”, 2018)

“Justice Reinvestment involves a redirection of money from prisons to fund and rebuild human resources and physical infrastructure in areas most affected by high levels of incarceration.” (ALRC “Pathways to Justice Inquiry”, 2018).[2]

Funding cuts are counterproductive given that they are made even when the Western Australian Office of Inspector of Custodial Services (“OICS”) acknowledged in a September 2014 report that a correlation exists between recidivism and the following factors:

- Age

- Prior prison admissions

- Level of educational attainment

- Substance abuse[3]

Reoffending Rates Remain High in WA Due to Inimical Treatment of Indigenous Youth

“For young Aboriginal people the rate of returning to prison is particularly alarming, being 25 percentage points higher than the non-Aboriginal recidivism rate. Only 26 percent of Aboriginal prisoners less than 24 years old were in prison for the first time, compared to 74 percent of non-Aboriginal prisoners in the same group.” (OICS Report, September 2014).

“More than half of sentenced youths in WA re-offended within 12 months and around one in every three youth offenders failed to complete their community-based orders.” (WA Today).

Banksia Hill Juvenile Centre is Punitive Rather than Rehabilitative:

“I feel Banksia Hill does not focus on any real rehabilitation, it’s just a punitive ‘lock them away, contain them’ until they either come back or turn 18 and go to adult prison… I feel that it’s a pipeline for adult prison.” (WA Today).

Detainees subject to torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment.

Amnesty International alleged that Banksia Hill breached international standards by subjecting two detainees to the following mistreatment. (Amnesty International Report, 16 January, 2018)

Solitary confinement: “Being held for weeks on end in a cell as small as a car parking space, with as little as 10 minutes out of the cell each day.”

Inhumane treatment: Detainees were denied access to basic services like a shower; forced to “earn their bedding”, fed through a grille in the door and received little or no exercise

Lack of access to services and programs: Throughout the 10-day period, detainees were provided with little or no access to a psychologist, despite the serious mental harm of this type of isolation.

Deprivation of family contact and education: (Amnesty International Report, 2018)

Education in BHJC have been recognised as substandard for many years. (Inspection of Banksia Hill Detention Centre, 2018)

“The Productivity Commission’s Report on Government Services, released Tuesday, showed 28 Aboriginal school-aged children and four non-Indigenous youths did not receive an education while at Banksia Hill Detention Centre in 2017-18.” (Western Australia Today, January 22, 2019).

Excessive use of restraints: Disproportionate use of handcuffs, spit-hoods and other restraints; restricted access to food and exercise and other “unprecedented techniques to control behaviour” which include “training the laser sights of shotguns on children. (ABC, July 2017)

Poor Mental Health amongst youth in Banksia Hill

89% of youth detained at Banksia Hill Nine have at least one form of severe brain impairment that is more likely to lead to problems with the law. (ABC, 2018)

Impairment manifests in weakened “language, executive function, memory and cognition, may contribute to offending behaviours and/or difficulties in negotiating all aspects of the justice system.” (ABC, 2018)

- 65% had at least three forms of severe brain impairment

- 23% had five or more forms of severe brain impairment

- 36% have foetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD), associated with the following negative outcomes:

- Failure to thrive, feeding problems, sensitivity to noise, touch and/or light and developmental delays

- Learning difficulties, memory problems, difficulties with social relationships, impulsiveness

- From 2016 through the first quarter of 2017, there were 272 examples of self-harm (a dramatic increase on the numbers reported in previous years) and six suicide attempts.

Conclusion

In order to combat Indigenous over-representation in WA, there needs to be a shift from a punitive model to a therapeutic approach that supports children who offend in the first place. The WA government needs to fund Indigenous-led programs, which will help Indigenous children to thrive in their communities rather than languish in detention centres.

Legislative success is dependent upon overcoming the tensions that exist among competing interests and expectations of immediate stakeholders. This involves a two-step process whereby:

- Normative shifts produce legal reform; and

- Legal change to produce behavioural change.

[1] Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: Bulletin 148 “Youth Detention Population in Australia, 2019”.

[2] Justice Reinvestment in Australia, Australian Government, Australian Institute of Criminology, 2018.

[3] Office of Inspector of Custodial Sentences, September 2014, pp(ii).

The Detention of Indigenous Youth is a Scourge on Australia

Detention in Australia

Throughout Australia, the age of Criminal Responsibility is set at just ten years of age. As such, “youth offenders” or “young people in detention” refers to individuals aged between 10 and 17 – a significant age gap given the difference in development, both physically and mentally, between a 17 year-old and a 10 year-old. In contrast, the global median age for criminal responsibility is 14.[1] There are two guiding principles upon which the Australian youth justice system is based, and which are incorporated in state and territory legislation. First, young people should be detained only as a last resort and secondly, this detention should only be for the shortest appropriate period.[2]

Australia has also ratified the following conventions, all of which pertain to the manner and circumstances in which youth are detained:

- the United NationsConvention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC)

- the Standard Minimum Rules for the Administration of Juvenile Justice (“the Beijing Rules”) 1985.

- the United Nations Guidelines for the Prevention of Juvenile Delinquency (“Riyadh Guidelines”) 1990.

- the United Nations Rules for the Protection of Juveniles Deprived of their Liberty

- the Optional Protocol to the Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment(OPCAT), 2017.

OPCAT requires Australia to monitor the rights of people deprived of liberty, including children in detention and aims to improve how people’s human rights are protected when they are detained. It does this by providing for a rigorous process of independent inspections of all places of detention in a country’s jurisdiction. In so doing, OPCAT enables a light to be shone on the conditions experienced by people in detention.

Youth Crime and Stakeholder Resistance

Stakeholders for Indigenous youth crime include: Indigenous youth offenders, their victims, the affected community and juvenile justice professionals.[3]

Each stakeholder “exerts a distinctive influence on the development of legal policy that aligns with their existing interests, either consciously or implicitly. The interplay of their diverse, often contradictory, reactions to regulatory change will collectively alter how the reforms transpire and can distort or undermine strived-for change.”[4]

[1] Heather McNeill. “Fears WA youth justice system is broken”. (Western Australia Today, January 22, 2019).

[2] Australia Institute of Health and Welfare. Bulletin 148, 2020, pp3.

[3] Sarah Xin Yi Chua and Tony Foley. “Implementing Restorative Justice to Address Indigenous Youth Recidivism and Over-Incarceration in the Act: Navigating Law Reform Dynamics.” Australian Indigenous Law Review, Vol 18. No. 1 (2014/2015), pp138.

[4] Sarah Xin Yi Chua and Tony Foley. “Implementing Restorative Justice to Address Indigenous Youth Recidivism and Over-Incarceration in the Act: Navigating Law Reform Dynamics.” Australian Indigenous Law Review, Vol 18. No. 1 (2014/2015), pp141.

The Three Main Approaches to Youth Crime

Restorative justice is a process where all parties with a stake in a particular offence come together to resolve collectively how to deal with the aftermath of the offence and its implications for the future.

Restorative justice depends upon a law reform strategy that:

- Addresses underlying colonial or racialized manner in which law reform is implemented; and

- Overcomes the tensions that exist between stakeholders about how the law should work in practice.

The Over-representation of Indigenous Youth in Detention

Although less than 5% of youth in Australia are Indigenous, they account for more than half of all youth detained in Australia.

In the June quarter 2019, young Indigenous Australians aged 10–17 were 21 times as likely as their non-Indigenous counterparts to be in detention on any average night.

- 57% of juveniles in detention in the June quarter 2019 were Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander though they made up just 6% of the Australian population aged 10–17

The Productivity Commission’s Report on Government Services of 2019 revealed that “Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youths in 2017-18 were nationally 24 times more likely to receive detention-based supervision than a non-Indigenous child.”

Cost of Indigenous Over-representation Generally

“It is estimated that the “total justice system costs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander incarceration in 2016 were $3.9 billion.”

When the costs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander incarceration are broadened beyond those directly related to the justice system to include things such as: the loss of productive output during incarceration, the cost of crime incurred by victims, the cost of increased mortality, excess burden of tax, and welfare costs, the costs of incarceration rise to $7.9 billion.

“As well as the cost of imprisonment to the State, imprisonment has immediate and ongoing financial and social costs for both the imprisoned person and their family.” (ALRC 2018), which can then project the underlying socioeconomic factors which are the greatest predictors of criminality to the next generation.

Indigenous Youth Re-offending Rates Remain Consistently High

“Aboriginal prisoners tended to be younger, have a higher security rating, and have a substance abuse problem, the analysis indicated that even after all these risk factors were accounted for, Aboriginal prisoners still reoffended at a greater rate compared to non-Aboriginal prisoners. These enduring differences are likely due to other social disadvantage risk factors that were not included in the analysis.” (OICS 2014)

Reasons for Indigenous Overrepresentation

- Colonial or racialized attitudes toward the implementation of reform which persist. Penal policies have been closely tied to imperialist and colonialist strategies which legitimated, and normalised, discriminatory penal practices toward Indigenous groups;

- Systemic bias in the operation of Australia’s laws;

- The discriminatory nature of policing in Indigenous communities and the criminalisation of Indigenous youth in Australia is widely acknowledged and continues to be a major obstacle to the legitimisation of mainstream legal policies.

- A ‘one-size-fits-all’ approachto crime prevention, rehabilitation and punishment, which remains committed to a mainstream criminal justice approach.

Indigenous Youth Suicide Rates

Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander suicides comprise 6% of Australia’s total suicides. Shockingly, however, 80% of child suicides aged 12 and below are by Aboriginal children. For the past decade, nearly 30% of the child suicides to age 17 were comprised of Indigenous children.[1]

While correlation does not necessarily equal causation, it is hard to ignore the link between the high percentage of First Nation youth suicides and the high incarceration rates given that youth who have been incarcerated are at a greater risk of developing depression and attempting suicide or self-harm. Incarceration also contributes to a break down in relationships and lower levels of education (The Conversation).

Western Australia – Australia’s Worst for Rates of Indigenous Incarceration

According to the most recent available census data, the population in Western Australia (WA) is just shy of 2.5 million. Of this 2.5 million, people of First Nations heritage account for only 3.1% of the population (Australian Bureau of Statistics).

WA imprisons Aboriginal people at a higher rate than any other state or territory, with 4.1% of its Aboriginal population behind bars, compared to 2.9% in the Northern Territory and a national rate of 2.6%.

Despite accounting for such a small part of the population, recent statistics supplied by the Department of Justice in WA show that within the adult prison population almost 40% of prisoners are of First Nations people (WA DOJ Adult Prisoners). The situation is even more disproportionate where youth offenders are concerned; over two-thirds (68.67% to be specific) of young people in custody in WA are First Nation people (WA DOJ Youth Detainees).

Reasons for Indigenous Over-representation in Western Australia

The Productivity Commission’s Report on Government Services of January 2019 revealed WA was one of only two jurisdictions nationwide to reduce funding to its youth justice services between 2016-17 and 2017-18, cutting $1.2 million from its detention and diversion programs, and community-based orders and services.

Funding cuts are also at odds with the Australian Law Reform Commission’s recommendations that “Commonwealth, state and territory governments should support justice reinvestment trials initiated in partnership with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, including through:

- facilitating access to localised data related to criminal justice and other relevant government service provision, and associated costs;

- supporting local justice reinvestment initiatives; and

- facilitating participation by, and coordination between, relevant government departments and agencies.”(ALRC “Pathway to Justice Inquiry”, 2018)

“Justice Reinvestment involves a redirection of money from prisons to fund and rebuild human resources and physical infrastructure in areas most affected by high levels of incarceration.” (ALRC “Pathways to Justice Inquiry”, 2018).[2]

Funding cuts are counterproductive given that they are made even when the Western Australian Office of Inspector of Custodial Services (“OICS”) acknowledged in a September 2014 report that a correlation exists between recidivism and the following factors:

- Age

- Prior prison admissions

- Level of educational attainment

- Substance abuse[3]

Reoffending Rates Remain High in WA Due to Inimical Treatment of Indigenous Youth

“For young Aboriginal people the rate of returning to prison is particularly alarming, being 25 percentage points higher than the non-Aboriginal recidivism rate. Only 26 percent of Aboriginal prisoners less than 24 years old were in prison for the first time, compared to 74 percent of non-Aboriginal prisoners in the same group.” (OICS Report, September 2014).

“More than half of sentenced youths in WA re-offended within 12 months and around one in every three youth offenders failed to complete their community-based orders.” (WA Today).

Banksia Hill Juvenile Centre is Punitive Rather than Rehabilitative:

“I feel Banksia Hill does not focus on any real rehabilitation, it’s just a punitive ‘lock them away, contain them’ until they either come back or turn 18 and go to adult prison… I feel that it’s a pipeline for adult prison.” (WA Today).

Detainees subject to torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment.

Amnesty International alleged that Banksia Hill breached international standards by subjecting two detainees to the following mistreatment. (Amnesty International Report, 16 January, 2018)

Solitary confinement: “Being held for weeks on end in a cell as small as a car parking space, with as little as 10 minutes out of the cell each day.”

Inhumane treatment: Detainees were denied access to basic services like a shower; forced to “earn their bedding”, fed through a grille in the door and received little or no exercise

Lack of access to services and programs: Throughout the 10-day period, detainees were provided with little or no access to a psychologist, despite the serious mental harm of this type of isolation.

Deprivation of family contact and education: (Amnesty International Report, 2018)

Education in BHJC have been recognised as substandard for many years. (Inspection of Banksia Hill Detention Centre, 2018)

“The Productivity Commission’s Report on Government Services, released Tuesday, showed 28 Aboriginal school-aged children and four non-Indigenous youths did not receive an education while at Banksia Hill Detention Centre in 2017-18.” (Western Australia Today, January 22, 2019).

Excessive use of restraints: Disproportionate use of handcuffs, spit-hoods and other restraints; restricted access to food and exercise and other “unprecedented techniques to control behaviour” which include “training the laser sights of shotguns on children. (ABC, July 2017)

Poor Mental Health amongst youth in Banksia Hill

89% of youth detained at Banksia Hill Nine have at least one form of severe brain impairment that is more likely to lead to problems with the law. (ABC, 2018)

Impairment manifests in weakened “language, executive function, memory and cognition, may contribute to offending behaviours and/or difficulties in negotiating all aspects of the justice system.” (ABC, 2018)

- 65% had at least three forms of severe brain impairment

- 23% had five or more forms of severe brain impairment

- 36% have foetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD), associated with the following negative outcomes:

- Failure to thrive, feeding problems, sensitivity to noise, touch and/or light and developmental delays

- Learning difficulties, memory problems, difficulties with social relationships, impulsiveness

- From 2016 through the first quarter of 2017, there were 272 examples of self-harm (a dramatic increase on the numbers reported in previous years) and six suicide attempts.

Conclusion

In order to combat Indigenous over-representation in WA, there needs to be a shift from a punitive model to a therapeutic approach that supports children who offend in the first place. The WA government needs to fund Indigenous-led programs, which will help Indigenous children to thrive in their communities rather than languish in detention centres.

Legislative success is dependent upon overcoming the tensions that exist among competing interests and expectations of immediate stakeholders. This involves a two-step process whereby:

- Normative shifts produce legal reform; and

- Legal change to produce behavioural change.

[1] Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: Bulletin 148 “Youth Detention Population in Australia, 2019”.

[2] Justice Reinvestment in Australia, Australian Government, Australian Institute of Criminology, 2018.

[3] Office of Inspector of Custodial Sentences, September 2014, pp(ii).